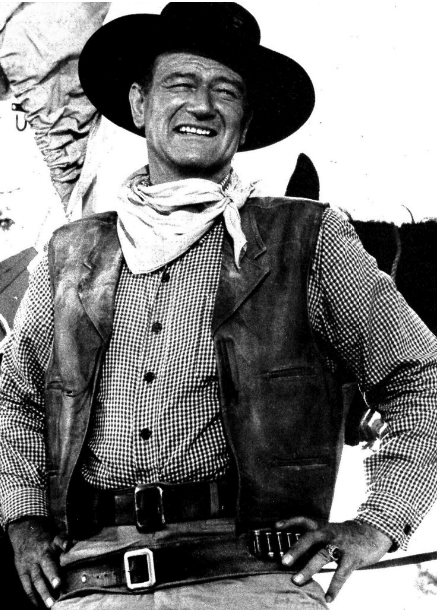

John Wayne symbolized the idealized American virtues of his period and represented the strong, reserved cowboy or military archetype.

However, his legacy is under question, and in recent years, an increasing number of people have questioned John Wayne’s macho persona both on and off the screen.

Even at the height of John Wayne’s fame, the fact that he opted not to fight in World War II infuriated many people.

Today, we have the explanation on why, and it might surprise you.

More than 16 million Americans fought in the US military during World War II, but John Wayne, real name Marion Mitchell Morrison, was not among them.

Hollywood was no different from the rest of society in that everyone was

expected to help with the war effort. Then why did “The Duke” not enlist? Many of his coworkers, including Jimmy Stewart, Clark Gable, and Henry Fonda, went into battle without thinking twice. Was John Wayne, as many have alleged, a draft evader?

The actor had just begun his career in Hollywood when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Although the 34-year-old Wayne was far from a household name, his self-confidence was growing as a result of his performance in John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939).

The box office smash Stagecoach elevated Wayne to stardom. With each passing year, his reputation in Hollywood strengthened. In light of this, World War II occurred at a very unfortunate time. Being drafted or joining the military may have potentially damaged his budding career.

Some stories claim Wayne’s only concern was losing his job.The 1940s saw “The Duke” begin to amass significant wealth, which was crucial given that his marriage to Josephine Alicia Saenz had ended and that he still had four children to raise.

Author Marc Eliot put up a different explanation for Wayne’s absence from the war in 2014.

Author Marc Eliot put up a different explanation for Wayne’s absence from the war in 2014. Eliot asserts that Marlene Dietrich and John Wayne had a relationship in his book “American Titan: Searching for John Wayne.” Wayne chose not to enroll and battle because he was worried about losing his friendship with Dietrich.

“When she came into Wayne’s life, she juicily sucked every last drop of resistance, loyalty, morality, and guilt out of him,” Eliot wrote.

Wayne applied for a 3-A draft deferment in 1943. He was granted a deferral from military service since he was the only supporter of a large family. Wayne may not be entirely to blame, though. In actuality, Republic Studio President Herbert Yates filed the deferment request on his behalf; he didn’t do it himself.

Gene Autry, who willingly enlisted in the Army Air Corps and attained pilot status, was Yates’ prized possession who had already been gone. He didn’t want to watch Wayne, his second source of income, don the uniform and vanish.

Wayne hoped to enlist after he filmed a few more movies, according to his buddies, but it never occurred. The Duke frequently wrote to the renowned and highly respected Irish director John Ford to inquire about joining Ford’s military regiment.

Wayne asked Ford in a 1942 letter, “Have you any ideas on how I should get in? If you could, would you want me to join your team and if so, how?

Ford produced a number of films for the Department of the Navy while working at the Office of Strategic Services. Additionally, he was on Omaha Beach on D-Day with his camera and directed the 1943 propaganda movie December 7th: The Movie.

Throughout the war, Ford would berate Wayne “to get into it”. The director complained that the actor was getting rich while other men sacrificed their lives on the shores of Europe and in the South Pacific.

Wayne’s application was criticized as being “half-hearted,” but he did get a good answer and a job offer from the Field Photographic Unit. Josephine, Wayne’s wife, received the letter, though. Her husband was never informed about it.

The famous actor was given a special 2-A status and deferred in “support of national interest,” so it appears that Hollywood, Wayne, and the government all agreed on what was best for everyone in the end.

The best thing Wayne, who starred in thirteen movies during the war, could do, he told pals, was to make pictures to encourage the troops.

Acting out other people’s deeds on the big screen, according to some, was the closest Wayne ever came to being in World War II.

To be fair, he did visit U.S. bases and hospitals in the South Pacific in 1943 and 1944, on an entertainment tour. The Hollywood star did his best to boost the morale of the troops, but it wasn’t easy for the famous actor to impress scarred combat veterans.

One time when Wayne walked out on stage in Australia, he received a chorus of boos from the audience.

“Duke largely could not get an officer’s commission to enter the military because he had an old injury, which would have kept anyone from being eligible, and also had four children. Also, the powers that be saw the immense contribution Duke could make on the screen to help national morale. His overall roles involved our exposure to what we were fighting abroad, and he also went on many trips drumming up support. He gets a bad rap for not being in the fight as others were, but let no one make that mistake. He was the real deal, no matter where he showed up,” film scholar James Denniston said in an attempt to put things in perspective.

In a New York Times Magazine article, author William Manchester gave an interesting testimony from his time serving¨in the Pacific. Manchester got wounded and had been evacuated when he got the chance to see John Wayne, the great American actor, and cultural icon.

”After my evacuation from Okinawa, I had the enormous pleasure of seeing Wayne humiliated in person at Aiea Heights Naval Hospital in Hawaii … Each evening, Navy corpsmen would carry litters down the hospital theater so the men could watch a movie. One night they had a surprise for us.

”Before the film, the curtains parted, and out stepped John Wayne, wearing a cowboy outfit – 10-gallon hat, bandana, checkered shirt, two pistols, chaps, boots and spurs. He grinned his aw-shucks grin, passed a hand over his face and said ‘Hi, ya guys!’ He was greeted by stony silence. Then somebody booed. Suddenly everyone was booing. This man was a symbol of the fake machismo we had come to hate, and we weren’t going to listen to him. He tried and tried to make himself heard, but we drowned him out, and eventually he quit and left,“ he said.

Two decades after his death, a BBC documentary called The Unquiet American shed new light on why Wayne didn’t serve during WWII.

According to the filmmakers, Wayne had a number of trivial excuses. One example? The actor claimed he didn’t have a typewriter to complete the appropriate forms.

“It was a purely careerist move. [Wayne] manipulated it so he didn’t have to sign up and could fill the vacuum left by the other Hollywood stars who did,” The Unquiet American’s producer James Kent told The Independent in 1997.

“Later he found himself a flag-waver and arch Commie-baiter with no military record.”

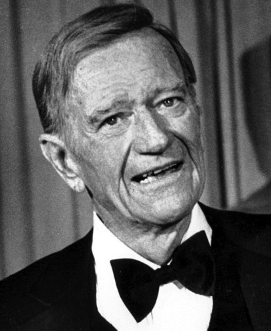

John Wayne’s decision not to serve would haunt him for the rest of his life, according to the book John Wayne: American. His post-war patriotism sprang from guilt. Many labeled Wayne a draft dodger.

“He would become a ‘superpatriot’ for the rest of his life trying to atone for staying home,” his widow, Pilar Wayne, wrote.

In 1979, John Wayne passed away from stomach cancer. President Jimmy Carter presented Wayne with the Presidential Medal of Freedom one year after his passing.

His World War II-era deeds played a significant role in the current tarnishing of his reputation as an American titan. A notorious Playboy interview from 1971